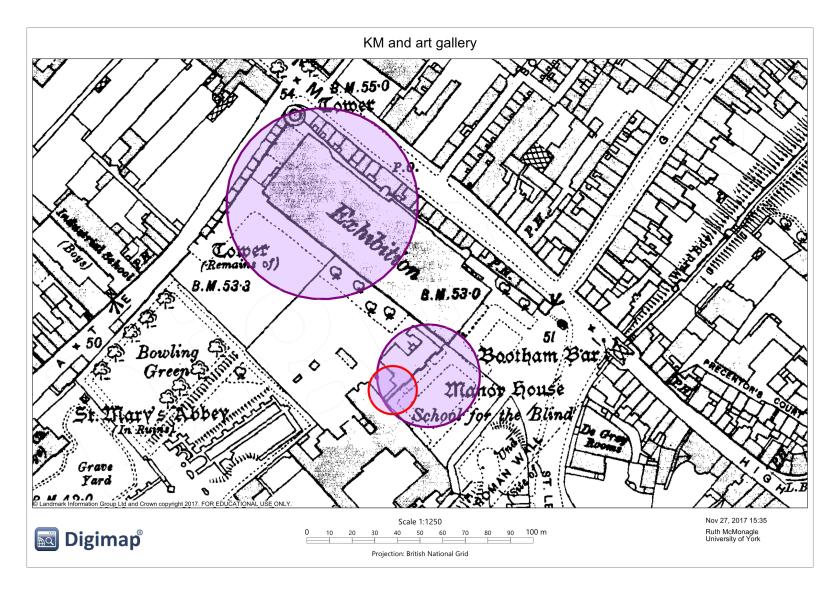

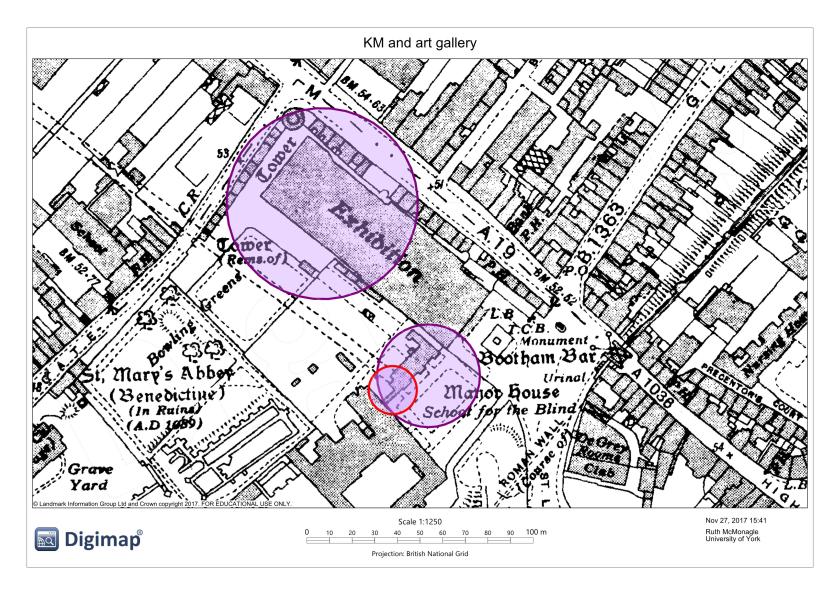

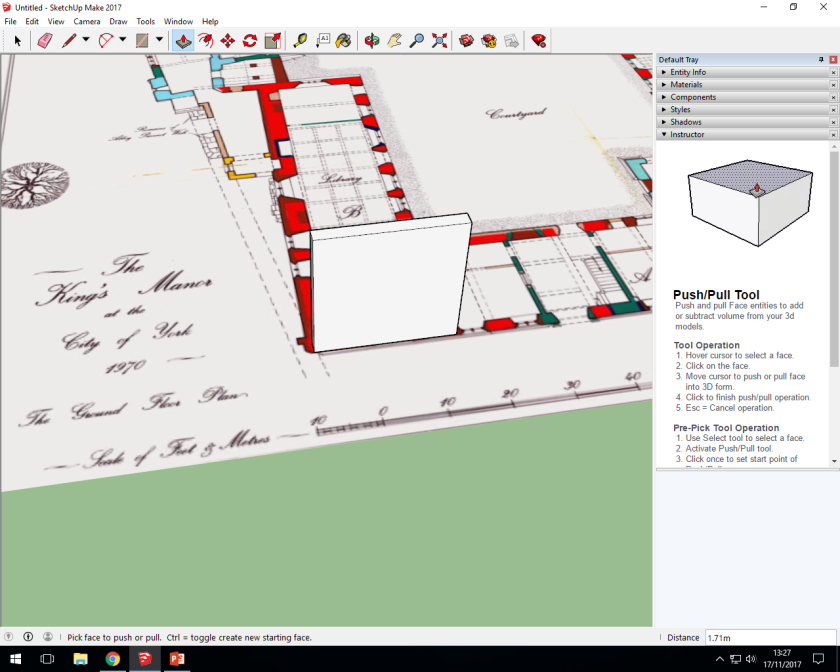

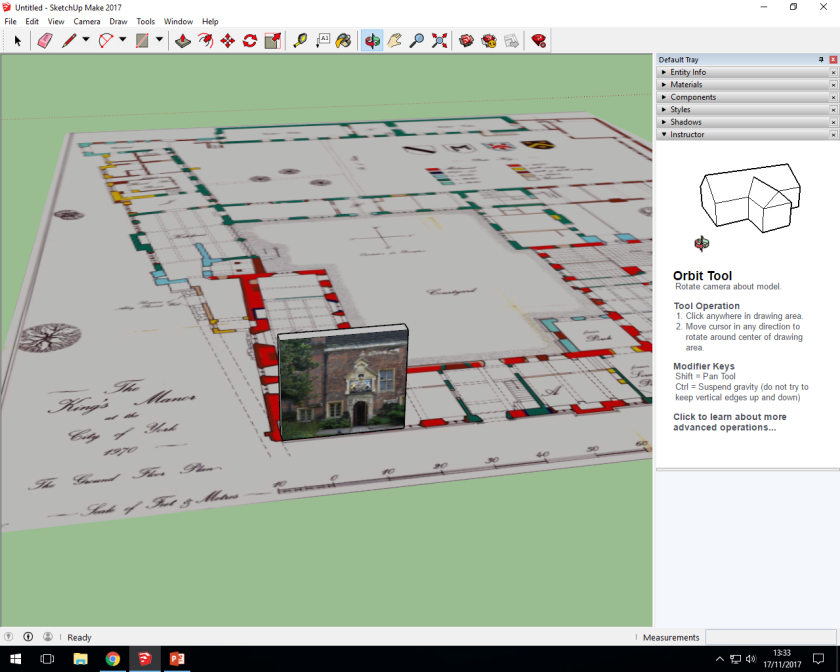

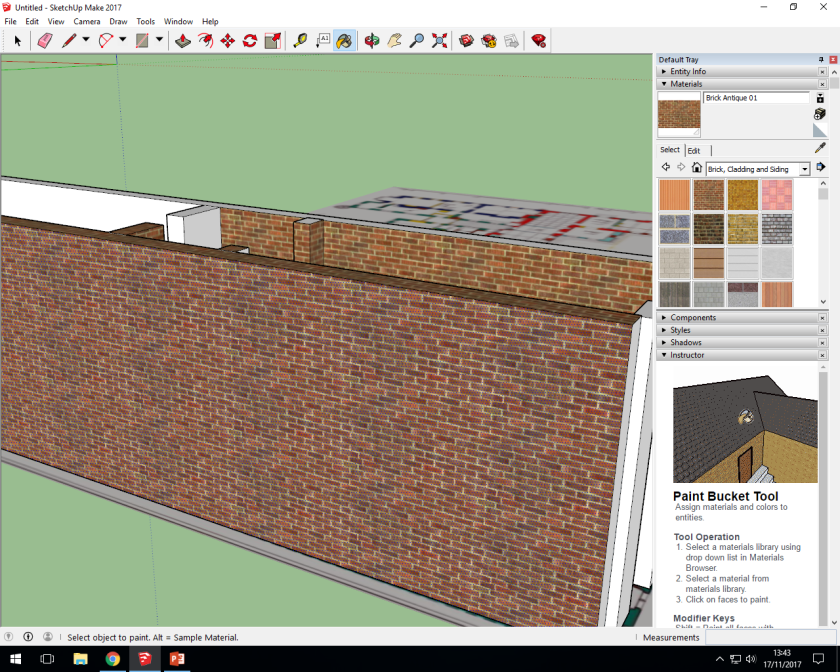

A current big focus in archaeology is video games and 3D reconstructions and environments (known as virtual archaeology) (Morgan, 2009, 471), so naturally we’ve been tasked with recreating our building (Kings Manor) in a 3D environment using a building tool called sketchup. Essentially the process involves uploading a map, and then using a tool to draw on the features which you finish by adding the right texture (one is bricks one is a photograph). The following images show my progress through the slightly finicky process:

Source: Author

I know what your thinking “wow, a door and a corridor, this is truly the best 3D reconstruction I’ve ever seen in my life” and while your assumed mental sarcasm might be right on how underwhelming my reconstruction is, 3D modelling could be a huge part of conveying information to the public through museums and online projects. Creating digital versions of archaeological sites has been the focus of quite a few projects, such as a recreation of Çatalhöyük (a neolithic site) in Second Life (Morgan, 2009) and a look into using motion capture to add humans to a 3D model of an Iron age round house (Woolford and Dunn, 2013). The Second life example is particularly interesting, as unlike most 3D modelling it is completely open to anyone with a computer and internet access, allowing things like virtual classes to take place on the recreation of the site (Morgan, 2009, 473-474), a level of freedom and openness that archaeology seems to rarely reach. Another fascinating aspect of this project was the humanity it added to the site, such as having trouble distinguishing the houses and whether or not that happened to the people that lived there (Morgan, 2009, 475), an aspect that the motion capture project also looked at, with strange issues such as when trying to map individuals sweeping them making very different movements depending whether or not they were in a reconstruction of a round house or a studio (Woolford and Dunn, 2013, 12). These aspects of Virtual archaeology are what makes it interesting, and how it can not only educate the public but also in turn inform archaeologists.

There are, however, issues with how the subject is approached and its longevity, the longevity being far more of an issue with the second life project rather than the motion capture project. It cost money to own land in Second Life (Morgan, 2009, 473) and to follow other options as buying domains, which means that when funding runs out these projects and areas can be lost forever. The problem with how Virtual archaeology is approached is a lot more subjective, especially within the realm of video games, and I personally feel archaeologists sometimes approach these projects without a proper understanding of the material. While the Çatalhöyük project understood the online world and how people interacted with it, the motion capture project had various issues such as stating that “Tools for capture and animation in video games are in

their infancy” (Woolford and Dunn, 2013, 2). This is a problem because 2 years prior L.A Noire was released, a best-selling game that was made famous by the fact that every single cut-scene in the game was motion capture- and while this may seems trivial the complete lack of knowledge about the market they were trying to break into is deeply concerning. Virtual archaeology and attempting to reach the public through the internet may be part of archaeology’s future, but understanding the virtual world needs to come first.

(Anon, ND) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L.A._Noire

Morgan, C.L., 2009. (Re)Building Çatalhöyük: Changing Virtual Reality in Archaeology. Archaeologies, 5(3), pp.468–487.

Woolford, K. & Dunn, S., 2013. Experimental Archaeology and Games: Challenges of Inhabiting Virtual Heritage. Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage, 6(4), pp.16:1–16:15.)